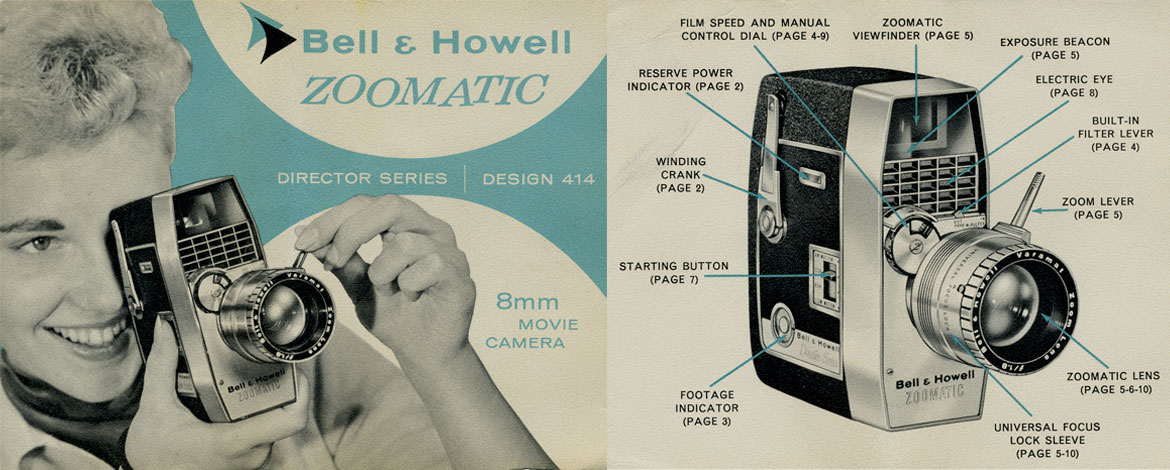

The Zoomatic Director Series 414

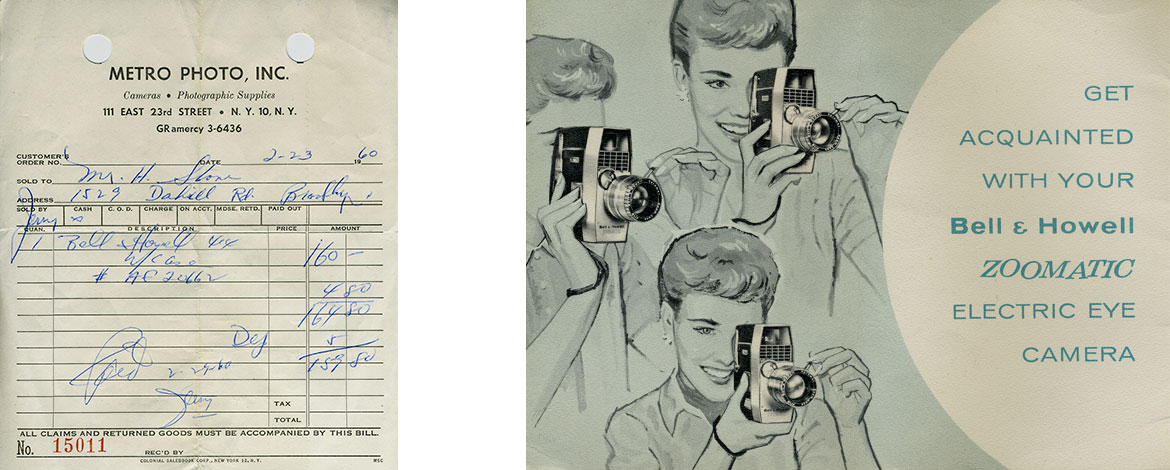

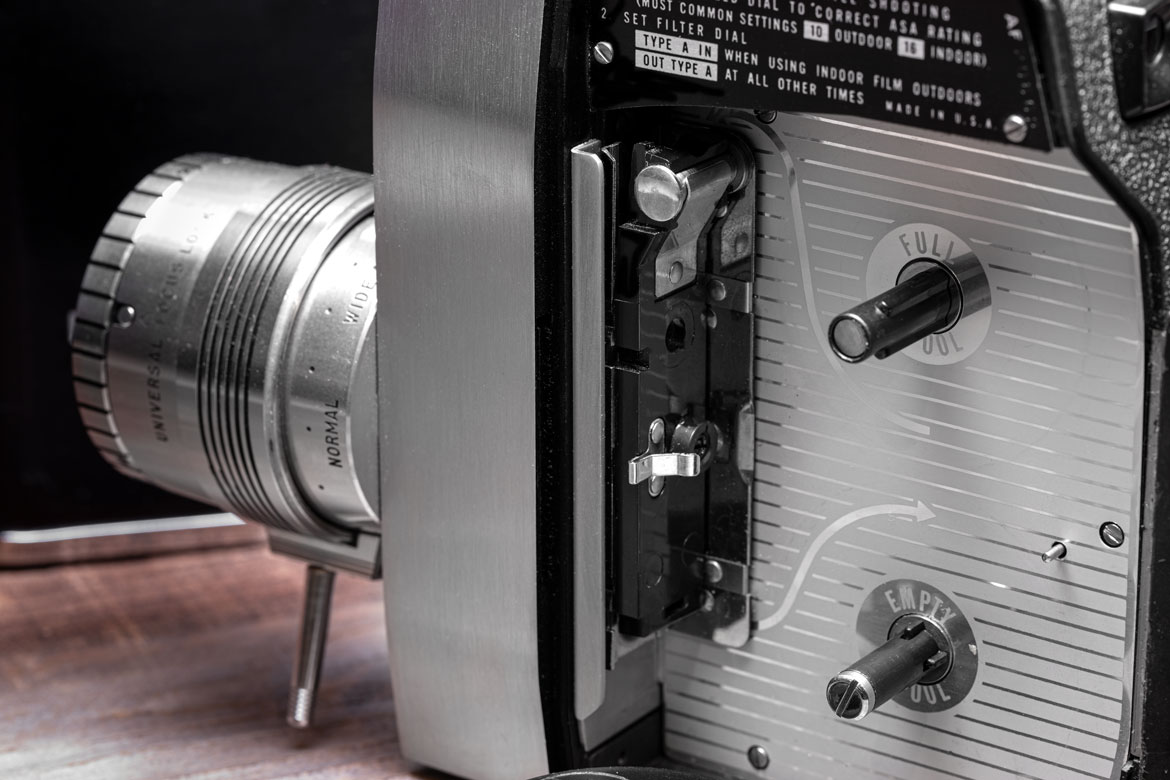

By comparison to today’s standards of advanced, high-speed, 4k+ resolution, HDR, ultra-compact, digital movie cameras, the Bell & Howell Zoomatic Director Series 414 8mm home movie camera is a behemoth relic of decades past. For most vintage movie camera collectors, the 414 makes a great conversation piece, moreover, a lethargic paperweight. However, when first introduced to the public in 1960, the 414 design was an expensive and much desired consumer-based camera, for capturing home movies on-the-go. For the Cold War nuclear family, with discretionary income, the 414 was a wise investment, for preserving memorable family experiences, for the future to come.

So, let’s go ahead and overload that Ford Galaxie Country Squire station wagon, sending the rear bumper to the asphalt while raising the headlights to the stars, with waxed canvas pup tents, army surplus sleeping bags, the all-steel outdoor kitchen, a Coleman galvanized metal ice chest, plenty of Coppertone suntan lotion, Off! insect repellent, tiki torches, the family dog, both kids (optional) and head out on the road, to shoot a home movie, for an adventure of a lifetime.

If unsure how to securely tie down the aluminum canoe to the station wagon’s roof, using the proper Boy Scout knot, do what everyone does…tie a redundancy of elementary knots and bring a Buck Knife, to cut it free once at camp.